The Great Paradox: When Markets Soar as Workers Fall

An Evidence-Based Analysis of AI Displacement, Tariff Shocks, and the Fracturing Social Contract

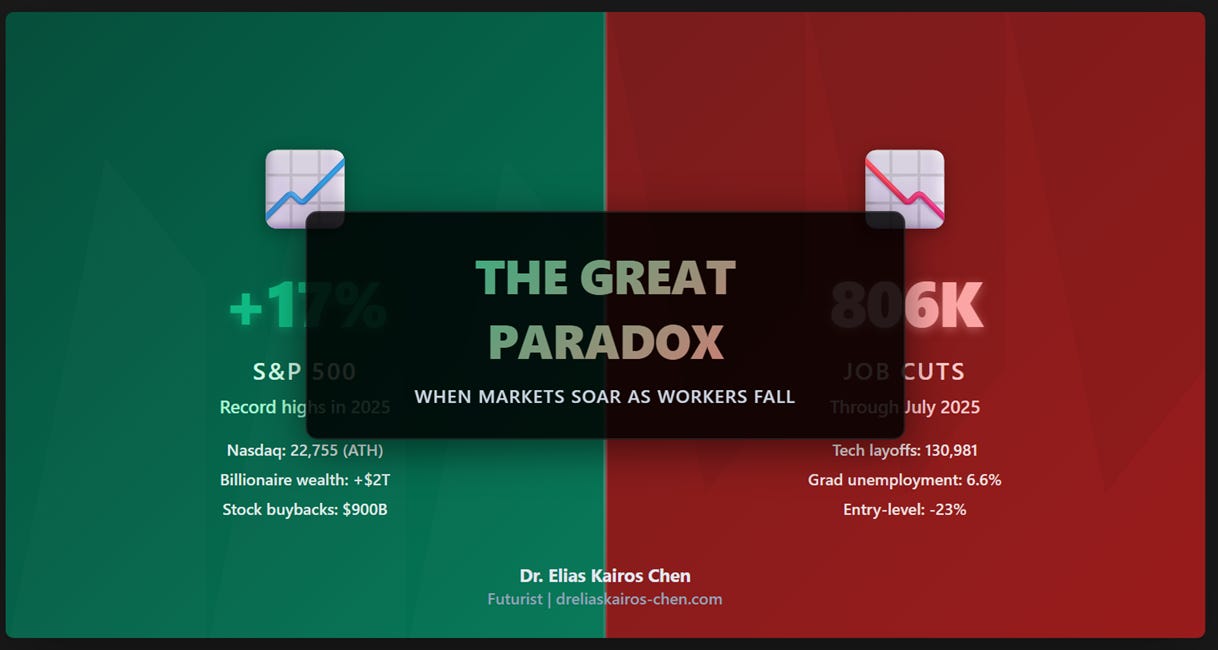

The S&P 500 reached 6,736 points on October 3, 2025—a 17% gain year-over-year. Graduate unemployment hit 6.6%, the highest in a decade. Over 130,000 tech workers lost their jobs in the first seven months of 2025 alone. This is not coincidence. This is policy.

I. The Paradox in Numbers

The American economy presents a statistical impossibility: record asset valuations coexisting with historic labor market distress.

On October 1, 2025, the S&P 500 closed at a record 6,711, capping a remarkable recovery that saw the index climb over 20% since its April low[1]. The Nasdaq Composite hit an all-time high of 22,755 in September, while the Dow Jones crossed 46,000 for the first time[2]. In 2023 alone, the Nasdaq gained approximately 40% even as major tech companies announced over 250,000 layoffs[3]. The world’s 500 richest individuals added $1.5 trillion in wealth in 2024, with a third of those gains concentrated in just five weeks following Trump’s election victory[4].

Yet beneath this market euphoria lies a different reality. Through July 2025, companies announced over 806,000 private-sector job cuts—the highest figure for that period since 2020’s pandemic devastation[5]. The tech sector alone shed 130,981 workers across 434 layoff events by mid-2025[6]. For recent college graduates, the unemployment rate reached 6.6% in 2025, the highest level in a decade outside the pandemic[7].

Most striking: for the first time since 1980, recent college graduates (ages 22-27) face higher unemployment than the national average—5.8% versus 4.2%[8]. Entry-level hiring has plummeted 23% compared to pre-pandemic levels[9].

This divergence is not cyclical. It is structural—the result of three simultaneous forces reshaping the economy.

II. The AI Displacement Machine

The rhetoric around artificial intelligence has always emphasized augmentation over replacement. Yet the evidence tells a different story—and 2025 marks the year companies stopped pretending otherwise.

When “AI-First” Means Human-Last

Swedish language-learning app Duolingo provides the clearest window into this transformation. In January 2024, the company cut 10% of its contractor workforce—primarily translators who created the app’s distinctive learning content[10]. By October, another round of writers were let go[11]. The pattern was clear: AI tools were replacing humans in content creation.

Then in April 2025, CEO Luis von Ahn made it explicit. In an internal memo (which he publicly shared after it began leaking), von Ahn declared Duolingo would become “AI-first” and would “gradually stop using contractors to do work that AI can handle.” The company instituted a new policy: headcount would “only be given if a team cannot automate more of their work”[12].

Von Ahn acknowledged the approach meant accepting “occasional small hits on quality” but emphasized the company would “rather move with urgency” than wait for AI to be perfect[13]. A former Duolingo contractor told journalist Brian Merchant: “We were encouraged to make the exercises fun. Now, the AI output is very boring... it absolutely makes mistakes”[14].

The displacement continues without reversal. By August 2025, von Ahn clarified that while full-time employees wouldn’t be laid off, contractor numbers would fluctuate based on “what AI can handle”—a distinction that offers little comfort to the gig workers already displaced[15].

The Code-Writing Threshold

Microsoft provides the most quantified view of AI’s displacement trajectory. By October 2022, GitHub CEO Thomas Dohmke revealed that AI was writing 40% of code in companies using GitHub Copilot—and projected that figure would reach 80% within five years[16].

The math is stark: if AI handles 80% of code generation, companies need far fewer junior and mid-level engineers. Microsoft’s actions confirmed this logic: the company cut over 15,000 jobs in 2025, explicitly stating that “AI tools like GitHub Copilot are reducing the need for layers of support teams”[17].

By July 2025, GitHub Copilot had reached 20 million users[18]. The market rewarded the efficiency: Microsoft’s Q1 2025 revenue hit $70.1 billion, up 13% year-over-year, and the stock reached all-time highs[19].

AI as Hiring Gatekeeper

E-commerce platform Shopify made the policy shift explicit in April 2025. CEO Tobi Lütke sent an internal memo mandating that teams “must demonstrate why they cannot get what they want done using AI” before requesting additional headcount or resources[20].

“What would this area look like if autonomous AI agents were already part of the team?” Lütke asked his teams. “This question can lead to really fun discussions and projects”[21].

Shopify’s headcount tells the story: from 8,300 employees to 8,100 over the past year, following earlier reductions of 14% in 2022 and 20% in 2023[22]. In January 2025, the company quietly laid off customer service staff[23].

Lütke framed AI usage as mandatory: “Using AI effectively is now a fundamental expectation of everyone at Shopify... I don’t think it’s feasible to opt out.” The company added AI usage questions to performance reviews[24].

IBM: The Vanishing HR Department

IBM’s transformation is even starker: the company laid off 8,000 employees, primarily from HR, and replaced them with an internal AI chatbot called “AskHR”[25]. The company described it as “modernizing workflows using automation” while redirecting spending to software engineers and data analysts.

The Pattern: Efficiency Rewarded, Employment Punished

The market’s response to layoffs has been striking. In high-profile cases, companies announcing major workforce reductions have seen their stock prices surge. Meta’s stock nearly tripled in 2023 after the company cut over 20,000 workers across two rounds of layoffs[26]. Salesforce saw its shares climb over 70% following significant job cuts[27]. The pattern is clear: Wall Street often rewards layoffs as evidence of “operational efficiency” and “shareholder value creation.”

Amazon CEO Andy Jassy was explicit in July 2025 internal memos: the company expects to “reduce our total corporate workforce as we get efficiency gains from using AI extensively”[28]. By mid-2025, Amazon had deployed over 1 million robots across its facilities[29]. UPS’s CEO similarly stated the company aims “to become less reliant on labor” through automation[30].

The data is unambiguous. From 2023 to mid-2025, over 27,000 job cuts were directly attributed to AI-driven redundancy[31]. But this vastly understates the true impact, as most companies avoid publicly linking layoffs to automation.

III. The Entry-Level Catastrophe

The labor market for recent graduates has collapsed with unprecedented speed. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports that recent college graduates (ages 22-27) face 5.3% unemployment in Q2 2025, with a 41% underemployment rate—meaning four in ten graduates work in jobs not requiring their degree[32].

Even the most educated face barriers. In a June 2025 survey, 58.9% of PhD students reported doubting they’re ready for the current market—not due to lack of skills, but lack of opportunities[33]. One in four Harvard MBA graduates remained unemployed three months after graduating in 2024[34].

The Burning Glass Institute found that 52% of college graduates now work in jobs that don’t require a degree at all—retail, food service, administrative support[35]. This represents a massive waste of human capital and a betrayal of the educational investment these individuals made.

The root cause is clear: entry-level work involves precisely the tasks AI excels at—data collection, transcription, basic analysis, customer service. As one economist explained, “A lot of entry-level work when you’re fresh out of college is knowledge-intensive jobs where you’re collecting data, transcribing data, and putting together basic visualizations”[36].

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei projects AI could eliminate 50% of entry-level white-collar jobs within five years, pushing unemployment to 10-20%[37].

IV. The IMF’s Warning: 40% of Jobs at Risk

The International Monetary Fund’s January 2024 analysis provides the most comprehensive assessment to date. Nearly 40% of global jobs will be affected by AI, with 60% exposure in advanced economies[38]. Unlike previous automation waves that displaced routine manual labor, AI targets cognitive work performed by high-income workers.

The scale of potential disruption is enormous. McKinsey estimates that 60-70% of work activities could be automated by current or near-future AI technologies[39]. Goldman Sachs projected in 2023 that generative AI could affect 300 million jobs globally[40]. These are projections, not certainties, but they reflect the assessment of leading economic institutions about AI’s transformative potential.

The IMF’s conclusion is stark: “In most scenarios, AI will likely worsen overall inequality”[41]. Workers who can harness AI will see productivity gains; those who cannot will fall behind. Crucially, productivity gains will boost capital returns disproportionately, favoring high earners and exacerbating wealth concentration.

A critical distinction from past technological revolutions: speed. While the steam engine, electricity, and early computers took decades to diffuse, generative AI can be deployed across entire sectors in months[42]. This compressed timeline leaves little room for organic labor market adjustment.

Research on displaced workers shows troubling long-term effects. Many face lasting income losses of 10-25% even years after displacement, with outcomes varying by industry, age, and skill level[43]. The combination of rapid displacement and incomplete recovery suggests a potential for sustained economic scarring.

V. The Tariff Tsunami

Compounding AI displacement is the most dramatic shift in U.S. trade policy in nearly a century. The average U.S. tariff rate stands at 18.9% as of September 2025, up from 2.3% in 2024. At the peak in April 2025, tariffs reached 27%—the highest level since the 1930s[44]. Monthly tariff revenue now exceeds $30 billion, compared to under $10 billion in 2024[45].

The Tax Foundation estimates these tariffs amount to an average tax increase of nearly $1,300 per U.S. household in 2025[46]. The Penn Wharton Budget Model projects even more severe damage: long-run GDP reduction of 6-8%, wage reduction of 5-7%, and middle-income household lifetime losses of $22,000 to $58,000[47].

The key finding: damage to economic output is twice as large as a revenue-equivalent corporate tax increase from 21% to 36%[48].

Labor markets are already feeling the impact. Retailers announced over 80,000 cuts through July 2025, up 250% year-over-year, as tariffs squeeze margins[49]. Manufacturing employment is declining despite the policy’s stated goal of protecting American manufacturing[50]. Business hiring has entered a “no hire, no fire” paralysis as companies await policy clarity[51].

Globally, J.P. Morgan now projects Q4 2025 real GDP growth of just 1.4%, down from 2.1% forecast at year’s start, with recessions expected in Canada and Mexico[52].

VI. The Wealth Concentration Accelerator

While workers absorb these shocks, wealth concentration has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age.

In 2024, billionaire wealth surged from $13 trillion to $15 trillion—the second-largest annual increase on record. Nearly four new billionaires were minted every week[53]. Elon Musk’s personal fortune grew from $229 billion to $442 billion, the largest personal fortune in human history[54]. President Trump’s net worth nearly doubled to over $7 billion—more than 137,000 times the average wealth of a family in America’s poorest 50%[55].

The long-term trend is even more troubling. The top 1% of Americans now own more wealth than the bottom 99% combined[56]. Between 1989 and 2016, the wealth gap between the richest 5% and second quintile rose from 114:1 to 248:1[57]. The top 1% captures 20% of total U.S. income while the bottom 50% receives just 10%[58].

Tax policy amplifies this concentration. The 2017 Trump tax cuts save households in the top 1% an average of $61,090 in 2025, and those in the top 0.1% an average of $252,300. Households in the bottom 60%? Less than $500 each[59].

This is not uniquely American. A January 2025 Pew Research survey of 36 nations found that 54% say the gap between rich and poor is a “very big problem,” while 60% believe “rich people having too much political influence” contributes greatly to inequality[60].

VII. Why Markets Celebrate Labor’s Decline

The apparent paradox resolves when we understand what stock prices actually measure: not societal wellbeing, but expected future corporate profits.

When Microsoft reports that AI writes 40% of its code and simultaneously lays off thousands of engineers, Wall Street sees lower labor costs, higher margins, and justified forward price-to-earnings ratios based on AI productivity gains. The stock market rewards layoffs with sharp price increases as evidence of “operational efficiency.”

The underlying economics reflect a broader shift. Since 2009, U.S. equity markets have more than quadrupled in value, while median wages have barely risen above inflation[61]. Since 1980, labor productivity has increased approximately 65%, while median wages have grown only about 15% after adjusting for inflation[62]. This productivity-wage divergence represents a fundamental transfer of economic gains from labor to capital. Meanwhile, S&P 500 firms spent over $900 billion on stock buybacks in 2022-2023, often exceeding their spending on worker training and development[63].

The AI boom has concentrated market gains dramatically. The “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks—Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Nvidia, Tesla—now comprise 34% of the S&P 500’s total value[64]. These companies are investing hundreds of billions in AI infrastructure. For shareholders, this represents euphoric expectations of a productivity revolution. For workers, it represents an existential threat of mass displacement.

Previous technological revolutions—steam, electricity, computing—eventually created more jobs than they destroyed. But AI differs in three critical ways: deployment speed (months, not decades), cognitive task replication (can replace knowledge workers), and capital-skill complementarity (AI pairs with high-skill workers, widening inequality)[65].

The result: an economy where productivity gains no longer translate to broad-based prosperity. Capital captures the gains; labor bears the costs.

VIII. The German Alternative: Codetermination

Not all advanced economies face this paradox with equal severity. Germany offers an instructive counterexample through its “codetermination” (Mitbestimmung) system, which requires worker representation on corporate boards.

Companies with 500+ employees must allocate one-third of supervisory board seats to worker representatives. For companies with 2,000+ employees, the requirement rises to half the board[66]. This gives workers formal voice in strategic decisions, including automation investments.

The empirical evidence is compelling. A 2020 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics examined a 1994 reform and found that codetermination had no impact on wages or labor share—workers don’t extract rents. But it increased capital investment by 8 percentage points, with zero or small positive effects on firm performance[67].

A 2021 NBER meta-analysis concluded: “Board-level and shop-floor worker representation cause at most small increases in wages, possibly lead to slight increases in job security and satisfaction, and have largely zero or small positive effects on firm performance”[68].

Why does this matter? When workers have board representation, companies cannot simply maximize short-term shareholder returns through mass layoffs. Strategic decisions must balance multiple stakeholder interests. This doesn’t eliminate AI adoption, but it slows labor displacement and ensures transition support.

As one German foundation leader explained: “Most German companies are content with this model because it leads to less internal conflict. They find it is easier to fulfill management strategy once they know the employees are behind it”[69].

IX. Rebalancing the Great Paradox: A Policy Playbook

The paradox of rising markets and falling workers is not inevitable. It is the outcome of choices about corporate governance, public policy, and the distribution of technological gains. But there are levers we can pull to realign prosperity with participation.

The following proposals are evidence-based and politically feasible in various combinations.

A. Immediate Labor Market Stabilization

1. Enhanced Unemployment Insurance Expand coverage to gig workers; raise replacement rates from 40-50% to 60-70% for the first six months; extend duration to 52 weeks for AI-displaced workers; add wage insurance for workers accepting lower-paying jobs[70]. Cost: ~$25 billion annually.

2. Sector-Based Transition Programs Establish “AI Transition Centers” in high-displacement regions; partner with community colleges for 6-12 month reskilling programs; focus on AI-complementary skills. Model: Singapore’s SkillsFuture and Denmark’s flexicurity system[71]. Cost: ~$15 billion annually.

3. Entry-Level Job Creation Federal infrastructure investment with apprenticeship requirements; tax credits for companies creating new entry-level positions; public sector expansion in education, healthcare, eldercare. Cost: ~$50 billion annually.

B. Tax and Redistribution Reform

4. Progressive Wealth Taxation Annual wealth tax: 2% on net worth $50M-$1B, 3% above $1B; close carried interest loophole; raise capital gains rates to match ordinary income for high earners; enforce 21% corporate minimum tax[72]. Revenue: ~$250 billion annually.

5. Earned Income Tax Credit Expansion Double EITC for workers without children; index to inflation; make refundable and advance-payable with monthly payments. Cost: ~$40 billion annually.

C. Trade and Industrial Policy Reform

6. Strategic Industrial Policy Scale back broad-based tariffs to <10% baseline; make targeted investments in critical sectors with labor standard requirements; create Trade Adjustment Assistance 2.0 with 2-year income support at 80% of prior wages[73]. Cost: ~$10 billion annually.

D. Corporate Governance and Worker Voice

7. Board-Level Worker Representation Phased implementation of codetermination: companies with 1,000+ employees must allocate 20% of board seats to worker representatives by 2027, rising to 33% by 2030. Model: German Mitbestimmung system[74].

8. Mandatory AI Impact Assessments Companies deploying AI systems affecting 100+ workers must conduct 90-day impact assessments; publicly disclose findings; provide retraining opportunities before layoffs; fund independent labor market research. Cost: ~$5 billion annually.

9. Profit-Sharing Requirements Companies with $1B+ revenue implementing AI-driven workforce reductions must share 10% of productivity gains with remaining workforce through bonuses or stock grants[75].

E. Social Insurance Modernization

10. Portable Benefits System Create universal benefits platform allowing gig workers to accumulate health insurance, retirement contributions, and unemployment insurance across multiple employers; funded by 5% payroll tax on all earned income[76]. Cost: ~$75 billion annually.

11. National Health Insurance Public option available to all; delinked from employment; funded through progressive income tax and employer contributions. Estimated cost: ~$150 billion annually (net of current subsidies).

F. Universal Basic Income Pilots

12. Federal UBI Pilot Program Five regions, 50,000 participants each, 5-year duration, $1,000/month unconditional cash with rigorous evaluation. Evidence from Kenya, Germany, and Stockton shows mixed but promising results on entrepreneurship, education, and mental health[77]. Cost: $3 billion annually for pilot.

G. National Reskilling Compacts

13. Large-Scale Public-Private Reskilling Singapore SkillsFuture model: lifelong learning credits ($500-3,000) for every citizen. Denmark flexicurity model: 90% wage replacement for 2 years with mandatory active programs. Regional AI Transition Funds financed by small levies on automation-intensive companies[78]. Cost: $50 billion annually.

H. Global Coordination

14. International Just Transition Compacts Embed Just Transition principles in OECD and G20 agreements; link trade access to worker rights commitments; create multilateral AI Impact Assessments similar to IPCC climate reports; establish ILO AI Convention for global minimum standards[79].

X. The Path Forward: A Narrow Window for Action

The next decade will determine whether this paradox hardens into permanent inequality or becomes the pivot point for a more inclusive economy.

The window is closing. Between 1929 and 1932, U.S. unemployment rose from 3% to 25%, contributing to the rise of extremist movements globally. Today’s AI displacement, while potentially slower, affects knowledge workers who form the middle class—the traditional stabilizing force in democracies. A hollowed-out middle class is a recipe for political instability.

The costs of inaction are severe: extended unemployment benefits, emergency social support, increased healthcare costs (unemployed workers have 3x depression rates), reduced consumer spending, lower tax revenue, family breakdown (unemployment increases divorce rates 30%), substance abuse, and rising mortality. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that every $1 spent on active labor market policies saves $3-5 in unemployment benefits and emergency support[80].

The models exist. Germany shows that worker representation and stakeholder capitalism can coexist with innovation—German DAX companies consistently outperform on long-term metrics while maintaining higher worker security[81]. Nordic countries demonstrate that strong social insurance can manage technological transitions without sacrificing dynamism—Denmark ranks 6th globally for innovation while maintaining generous unemployment benefits[82].

The implementation timeline must be aggressive:

2025-2026: Enhanced unemployment insurance; AI transparency requirements; federal pilot programs; emergency displaced worker support

2026-2028: Worker board representation phased in; progressive wealth taxation; corporate governance reforms; national reskilling infrastructure

2028-2030: UBI scaled nationally based on pilots; international AI governance coordination; full retraining implementation; Sovereign AI Fund established

2030+: Evaluate and adjust; potential work-time reduction if productivity gains sufficient; continued social contract evolution

The cost of this full agenda: approximately $400-500 billion annually, or 1.5-2% of GDP. This is comparable to New Deal spending (adjusted for today’s economy) and less than the 2017 tax cuts cost in foregone revenue[83].

The paradox is real. But it is also reversible.

We can have innovation without immiseration. We can have productivity growth without social decay. We can have capitalism that serves democracy rather than undermining it.

But only if we choose to act. The data demands it. The evidence supports it. The window is open, but closing fast.

The time is now.

Dr. Elias Kairos Chen is a futurist analyzing the intersection of technology, economics, and policy. Visit dreliaskairos-chen.com for more insights on navigating the future of work.

Endnotes

[1] CNBC Market Data, “Stock Market Today Live Updates,” October 1, 2025

[2] CNBC Market Data, “Nasdaq Closes at Record High,” September 12, 2025

[3] Bloomberg, Reuters, Layoffs.fyi; Nasdaq performance data 2023; tech sector layoff tracking

[4] Oxfam International, “Takers Not Makers” (2025); Bloomberg Billionaires Index

[5] Challenger, Gray & Christmas, “Job Cut Report: July 2025”

[6] TrueUp.io, “Tech Layoffs 2025” (accessed September 2025); Layoffs.fyi tracking data

[7] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; Wall Street Journal analysis, “Class of 2025 Faces Worst Job Market in Decade”

[8] Oxford Economics, “Graduate Labor Market Analysis Q2 2025”

[9] LinkedIn Economic Graph, “Entry-Level Hiring Index” (March 2025)

[10] TechCrunch, “Duolingo cut 10% of its contractor workforce as the company embraces AI,” January 9, 2024

[11] Brian Merchant, “The AI jobs crisis is here, now,” Blood in the Machine, May 2, 2025

[12] Fortune, “Duolingo CEO says he’s getting rid of contract employees and replacing them with AI,” April 30, 2025

[13] The Register, “Duolingo ditches more contractors in ‘AI-first’ refocus,” April 29, 2025

[14] Brian Merchant, “The AI jobs crisis is here, now,” Blood in the Machine, May 2, 2025

[15] Fortune, “Duolingo CEO admits his controversial AI memo ‘did not give enough context,’” August 18, 2025

[16] CNBC, “Microsoft’s GitHub Copilot AI is making rapid progress,” October 14, 2022

[17] Business Insider/CNBC, “Microsoft Layoffs 2025,” May 2025; company internal communications

[18] TechCrunch, “GitHub Copilot crosses 20M all-time users,” July 31, 2025

[19] Microsoft Q1 FY2025 Earnings Report

[20] TechCrunch, “Shopify CEO tells teams to consider using AI before growing headcount,” April 7, 2025

[21] Ibid.

[22] Business Today, “’AI use is no longer optional at Shopify’ declares CEO Tobi Lütke,” April 8, 2025

[23] Business Insider, cited in TechCrunch article, April 2025

[24] Inc., “Shopify CEO to Employees: Use AI Now,” April 8, 2025

[25] CNBC, “IBM Layoffs: 8,000 Jobs Cut as AI Takes Over HR Functions,” 2025

[26] Meta Platforms stock performance 2023; Bloomberg, Reuters reporting on Meta layoffs

[27] Salesforce stock performance 2023-2024; financial press reporting

[28] Internal Amazon memo cited in multiple sources including CNBC, July 2025

[29] CNBC, “Amazon Deploys 1 Million Robots Across Facilities,” April 17, 2025

[30] UPS Q2 2025 Earnings Call transcript

[31] Challenger, Gray & Christmas, “AI-Related Job Cuts Report, 2023-2025”

[32] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates,” Q2 2025

[33] TopResume, “Graduate Job Search 2025: Confidence Crisis Hits New Grads,” June 2025 (survey of 1,000 graduates)

[34] Victoria Etherton (career.io), cited in TopResume report; LinkedIn post February 2024

[35] Burning Glass Institute, “The Permanent Detour” (2022-2024 analysis)

[36] Tristan L., Lightcast economist, quoted in TIME, “How to Land a Job in 2025,” June 6, 2025

[37] CNN interview with Anderson Cooper, cited in CNN Business, “Anthropic CEO Warns AI Could Wipe Out Half of Entry-Level Jobs,” June 2025

[38] IMF Staff Discussion Note, “Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work” (SDN 2024/001), January 2024

[39] McKinsey Global Institute, “The Economic Potential of Generative AI” (2023)

[40] Goldman Sachs, “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth” (2023)

[41] IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, IMF Blog, “AI Will Transform the Global Economy,” January 14, 2024

[42] IMF Staff Discussion Note, “Broadening the Gains from Generative AI” (SDN 2024/002), June 2024

[43] OECD Employment Outlook; Brookings Institution research on displaced workers’ long-term earnings trajectories

[44] Tax Foundation, “Trump Tariffs: The Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War” (updated September 2025)

[45] U.S. Customs and Border Protection monthly collections data; Tax Foundation analysis

[46] Tax Foundation, “Trump Tariffs” report (September 2025)

[47] Penn Wharton Budget Model, “The Economic Effects of President Trump’s Tariffs,” April 22, 2025

[48] Ibid.

[49] Challenger, Gray & Christmas, “Retail Sector Layoffs Report,” July 2025

[50] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation Reports (2025)

[51] Jefferies Economic Research, quoted in CNBC, “’No Hire/No Fire’ Market,” May 2025

[52] J.P. Morgan Global Research, “US Tariffs: What’s the Impact?” (Q4 2025 projections)

[53] Oxfam International, “Takers Not Makers” (2025)

[54] Bloomberg Billionaires Index (2024-2025)

[55] Forbes estimates; Census Bureau wealth data

[56] Federal Reserve, “Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S.” (2024)

[57] Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, 1989-2016

[58] Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2024”

[59] Tax Policy Center, “Distributional Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” (2025 estimates)

[60] Pew Research Center, “Global Attitudes on Inequality” (January 2025)

[61] Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED); Bureau of Labor Statistics wage data

[62] Economic Policy Institute, “The Productivity-Pay Gap” (updated 2025)

[63] S&P Dow Jones Indices; Bloomberg analysis of share buyback data 2022-2023

[64] S&P Global Market Intelligence (September 2025)

[65] Acemoglu & Restrepo, “Automation and New Tasks,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (2019); updated analysis 2024

[66] German Co-Determination Act (Mitbestimmungsgesetz); Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs

[67] Jäger, Schoefer & Heining, “Labor in the Boardroom,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (2020)

[68] NBER Working Paper 29537, “What Do We Learn from Codetermination?” (2021)

[69] Hans-Böckler-Stiftung research, quoted in various academic sources

[70] Congressional Research Service, “Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits” (2024); cost estimates from CBO

[71] Singapore SkillsFuture program documentation; Danish Ministry of Employment flexicurity analysis

[72] Economic Policy Institute revenue estimates; Tax Policy Center modeling

[73] Peterson Institute for International Economics, “Trade Adjustment Assistance Reform Proposals” (2024)

[74] Based on German Mitbestimmung implementation; adapted for U.S. corporate law

[75] Proposed legislation similar to Reward Work Act (various versions 2018-2024)

[76] National Academy of Social Insurance, “Portable Benefits in the 21st Century” (2023)

[77] GiveDirectly Kenya UBI study; Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration; German Mein Grundeinkommen results

[78] Singapore SkillsFuture program costs; Danish flexicurity system expenditure data

[79] International Labour Organization, “Global Commission on the Future of Work” (2019); proposed AI Convention framework

[80] Congressional Budget Office, “The Effects of Active Labor Market Policies” (2023)

[81] Boston Consulting Group, “Long-Term Performance of German DAX Companies” (2024)

[82] Global Innovation Index 2024; OECD unemployment benefit replacement rate data

[83] Congressional Budget Office revenue estimates; New Deal spending adjusted for 2025 GDP